Name: Christopher Marlowe.

Born: 6 February 1564, Canterbury, England.

Died: Late May 1593, Deptford, England – Maybe.

Buried: St. Nicholas’ churchyard, Deptford.

It is ironic that while we seem to possess more basic biographical information regarding Christopher Marlowe than we do of most of the Elizabethan era’s other dramatists, there is a greater sense of mystery about him than of any other poet as well; this is due to his likely secretive and extensive work as a spy on behalf of Queen Elizabeth, of which necessarily we expect to find little obvious evidence; and the puzzling circumstances regarding what appear to be his murder in 1593.

Christopher Marlowe was born on 6 February 1564 at Canterbury, the son of a shoemaker. After attending King’s School in the same city, he went on to Cambridge as one of the scholars sponsored by Archbishop Parker of Canterbury. Marlowe matriculated from Corpus Christi College in 1581, and received a B.A. degree in 1584. He continued his studies, presumably with an intent to earn an M.A. degree next.

Marlowe may have been recruited during this period to become a secret agent, serving Queen Elizabeth’s Secretary of State Francis Walsingham, who among his other responsibilities had to provide for the queen’s safety in an era of Catholic unrest and political assassination. One of the more amusing stories told about Marlowe is that he was absent for so many of his classes that the college threatened to not allow him to graduate in 1587 with his M.A.; but a letter sent from the government, signed by many of Elizabeth’s top officials, including the Lord Chancellor, Lord Treasurer, Lord Chamberlain, and the Archbishop of Canterbury (now that’s star power!) caused Cambridge to relent, and Marlowe graduated accordingly.1

Marlowe may have been recruited during this period to become a secret agent, serving Queen Elizabeth’s Secretary of State Francis Walsingham, who among his other responsibilities had to provide for the queen’s safety in an era of Catholic unrest and political assassination. One of the more amusing stories told about Marlowe is that he was absent for so many of his classes that the college threatened to not allow him to graduate in 1587 with his M.A.; but a letter sent from the government, signed by many of Elizabeth’s top officials, including the Lord Chancellor, Lord Treasurer, Lord Chamberlain, and the Archbishop of Canterbury (now that’s star power!) caused Cambridge to relent, and Marlowe graduated accordingly.1

Marlowe went to London, where he immediately entered the theatrical profession, joining the Lord Admiral’s Company of Players; but other than what is evidenced by his dramatic writing, very little is known about Marlowe’s activities in London or in the theatre generally. We do know he was friends with Sir Walter Raleigh, and roomed with playwright Thomas Kyd.

Marlowe seems to have developed a reputation for being a free-thinker and perhaps an atheist – a dangerous condition for any Londoner to have during Elizabeth’s reign. In early 1593, the formidable Star Chamber began to take an interest in the young dramatist. While searching the flat of Marlowe and Kyd, investigators found some incriminating papers apparently belonging to Kyd. Marlowe’s roommate was apprehended and rigorously tortured, but Kyd managed to maintain his own innocence, claiming Marlowe was the owner of the evidence in question.1

Marlowe was in turn arrested 20 May 1593, but surprisingly, unlike Kyd, was immediately freed on bail on the condition that he check-in daily with the court.1

The last thing known about Marlowe was that he was reported slain at Deptford about a week or so after his arrest; as the editor of the Mermaid edition of Marlowe’s plays, Havelock Ellis, wrote, at Deptford “there was turbulent blood there, and wine; there were courtesans and daggers.”2

Conspiracy theories have abounded; not everyone believed Marlowe had actually died, just as many still believe today that John F. Kennedy and Elvis Presley are still alive. It has been argued that the government faked Marlowe’s murder to allow him to continue his espionage activities even more discreetly, and even that Marlowe arranged the hoax himself.

On top of this, a whole cottage-industry has grown up around the theory that Marlowe went on to write all of the plays attributed to Shakespeare.3

On top of this, a whole cottage-industry has grown up around the theory that Marlowe went on to write all of the plays attributed to Shakespeare.3

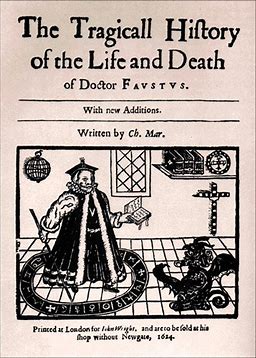

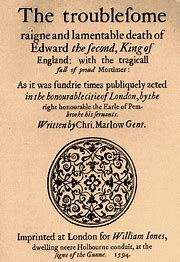

Marlowe’s plays are powerful and hard-hitting; though he lacked the depth and profundity of Shakespeare, who admired and emulated him, it must be remembered that Marlowe practically invented the era of Elizabethan Drama. His first major play, Tamburlaine the Great, was unlike anything ever seen on stage before, a boisterous production featuring a swaggering giant of a man who toppled kingdoms and conquered much of Asia in the 14th century. Tamburlaine was also the first publically performed play to be written in unrhymed iambic pentameter – blank verse – which, almost solely because of the success of this play, became the standard for English drama for as long as English playwrights wrote in verse.

For extensive research and in-depth investigation into the life and works of Christopher Marlowe, visit the website of The Marlowe Society:

http://www.marlowe-society.org/

Footnotes:

1. Information in these paragraphs was adapted and summarized from more expansive articles appearing at the website of the Marlowe Society: see the section titled The Government Agent at http://www.marlowe-society.org/christopher-marlowe/life/government-agent/.

2. Ellis, Havelock, ed. The Best Plays of the Old Dramatists: Christopher Marlowe. London: Viztelly & Co., 1887.

3. See, for example, the following websites:

a. www.shakespeareanauthorshiptrust.org.uk/pages/candidates/marlowe.htm.

b. www.themarlowestudies.org/index.html.