Name: John Lyly.

Born: 1553 / 1554, Kent, England.

Died: c. 20 November 1606.

Buried: 20 November 1606, St. Bartholomew the Less, London.

Life of John Lyly

John Lyly was the first superstar dramatist of the Elizabethan era, though his brilliance shone more like a shooting star than the sun.

Born in about 1553 in Kent, Lyly earned a B.A. from Magdalen College in Oxford, and an M.A. from Oxford, although as the 17th century antiquarian Antony Wood wrote, Lyly did “in a manner neglect academic studies.”1

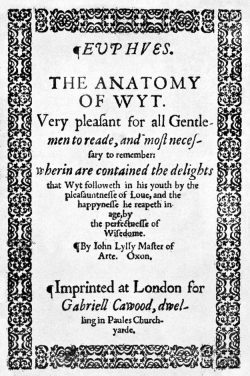

Lyly then moved to London where he spent decades waiting fruitlessly for a rewarding appointment from the court. Turning to writing, Lyly published his first novel, Euphues, or the Anatomy of Wit, in 1578. The book, a sort of travel and romance adventure, was an immediate sensation, and he followed up his success with the equally popular Euphues and His England in 1580. The reason for the interest in the books, however, was the unusual style of the writing, more so than the stories themselves, and we will discuss this style in a moment.

It is possible that Lyly had been led to expect he would be appointed to be Master of the Revels, the official charged with reviewing and licensing plays in London, whenever the next vacancy arose. However, his dreams were constantly disappointed, when first in 1578 Thomas Blagrave was appointed to the office after the death of its previous holder, and then again in 1579 when the position was granted to Edmund Tylney, who would hold it for 31 years!

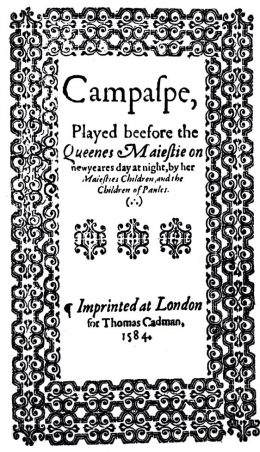

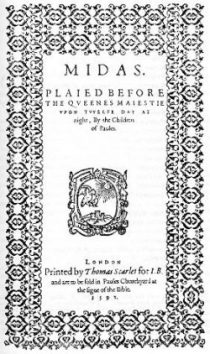

In the meantime, Lyly turned to drama, and from 1584 to 1592 he wrote and directed about 7 or 8 plays, which delighted London audiences as much as his books had. In fact, the plays were all performed privately for Queen Elizabeth, after having been publically presented and practiced, and all were acted by children’s troupes. The sovereign appears to have enjoyed them as much as the common London citizen did. All the plays but one (The Woman in the Moon) were in prose.

Despite the success of his literary work, however, Lyly never received an office of substance from the queen. Two pitiful letters remain extent, in which we see Lyly embarrassingly grovel for a job; the reader will cringe as he or she reads Lyly’s words: “Thirteen years your highness’ servant but yet nothing…A thousand hopes, but all nothing; a hundred promises but yet nothing…”2

Despite the success of his literary work, however, Lyly never received an office of substance from the queen. Two pitiful letters remain extent, in which we see Lyly embarrassingly grovel for a job; the reader will cringe as he or she reads Lyly’s words: “Thirteen years your highness’ servant but yet nothing…A thousand hopes, but all nothing; a hundred promises but yet nothing…”2

Lyly abandoned drama after 1592, but both his works and reputation “steadily declined in influence and reputation”3, until he died poor and neglected in 1606 (though he did serve in Parliament occasionally between 1589 and 1601). Our hero was buried on 20 November 1606 at St. Bartholomew the Less in London.

A contemporary of Lyly’s described him as a small man, married, and with a penchant for tobacco. He appears to have had at least two sons, both of whom died as infants, both named John.

Lyly’s Euphuism

Lyly’s writing style, which so took London by storm, was known as euphuism, named after his novels. The style is a highly affected one, and is marked by three primary characteristics: (1) an effusion of short parallel phrases and sentences; (2) the incorporation of fantastic similes taken from natural history and mythology; and (3) the frequent use of alliteration.

Regarding Lyly’s use of parallel phrases, a few examples from his first Euphues novel will suffice; consider the novel’s opening sentence: “Here dwelt in Athens a young gentleman of great patrimony, and of so comely a personage, that it is doubted whether he were more bound to nature for the lineaments of his person, or to Fortune for the increase in his possessions.” Shortly afterwards we get “So likewise is the disposition of the mind, either virtue is overshadowed with some vice, or vice overcast with some virtue.”

As to Lyly’s use of fantastic similes, Lyly primarily drew ideas from the encyclopedic work Natural History, written by Pliny the Elder in the 1st century A.D. Pliny’s work today is famous for its outrageously incorrect descriptions of nature. Thus in the prologue of Sapho and Phao, Lyly writes that where “the bee can suck no honey, she leaveth her sting behind, and where the bear cannot find origanum to heal his grief, he blasteth all other leaves with his breath.”

Euphuism became so popular that it was said to give “the tone to the conversation of the court of Queen Elizabeth”4. But like any fad which comes on so quickly, there was a backlash, and as newer and more modern writers like Shakespeare assumed the mantle of leadership in Elizabethan literature, euphuism quickly came into disfavor, and became the target of mocks and jibes by other writers.

Even today, Lyly’s reputation has suffered from his inevitable linking with euphuism; as the Dictionary of National Biography of the late 19th century put it, the “monotonous structure of his sentences wearies the modern reader.”5

Much as we may laugh at Lyly’s writing style today, it is necessary to recognize Lyly’s importance in the history of Elizabethan drama; his dialogue, characterizations, and plotting, though “still a long way removed from…Shakespeare”6, gave to London society entertainment which was a great advancement from what had come before it, and provide an important and undeniable link between the cruder plays that preceded Lyly’s, and the genius that came after them.

Recent Lyly editor Carter Daniel defends Lyly’s use of euphuism, asking us to take Lyly in the context of his time and individual situation; after all, Lyly, unlike any other playwright of the era, was writing specifically for the queen’s entertainment, and since this is what she liked, this is what he gave her.7

Recent Lyly editor Carter Daniel defends Lyly’s use of euphuism, asking us to take Lyly in the context of his time and individual situation; after all, Lyly, unlike any other playwright of the era, was writing specifically for the queen’s entertainment, and since this is what she liked, this is what he gave her.7

A more relevant criticism of Lyly’s plays is that they are completely lacking in gravity; their reliance on classical myth, the language that is both light and affected, the short scenes that come and go with great rapidity, and the lack of any weightiness in subject, give them an air of frivolousness; but here again, Lyly, as any successful tradesman might do, was giving his employer what she wanted to see, and as he did not wish to offend his sovereign, he had to stay away from any material that might bring criticism down on his head.

As the canon of Lyly’s work is small, and as his plays are short (about half the length of the plays of his successors’), you, the modern reader should make sure to incorporate the occasional Lyly play into your diet; the plays are brisk and often funny, and because Lyly’s euphuism is so unusual, you may find it highly entertaining (at least for a little while at a time), and his works can serve as amusing intermissions between the denser and weightier works of Shakespeare and Lyly’s other contemporaries and successors.

Plays of John Lyly

All of John Lyly’s plays are in prose, except for The Woman in the Moon, his only verse play.

- Campaspe (1584), a history play – sort of – starring Alexander the Great, and a host of famous philosophers. Perhaps Lyly’s funniest play.

- Sapho and Phao (1582-84), a classical play with gods and goddesses.

- Endimion, the Man on the Moon (1588), a classical play. Daniel calls this “Lyly’s masterpiece” (p. 195).

- Gallathea (1588), a pastoral comedy. Daniel describes this play as possessing “intrinsic beauty” (p. 143).

- Midas (1589), a mythological play.

- Mother Bombie (1594), a comedy in modern times.

- The Woman in the Moon (1597), another pastoral comedy.

- Love’s Metamorphosis (date uncertain), one last pastoral comedy. Daniel describes this play as “one of the most unjustly neglected plays in English literature” (p. 314).